Opportunity Culture® Dashboard

Two Independent Studies Find Large Academic Gains in Opportunity Culture®

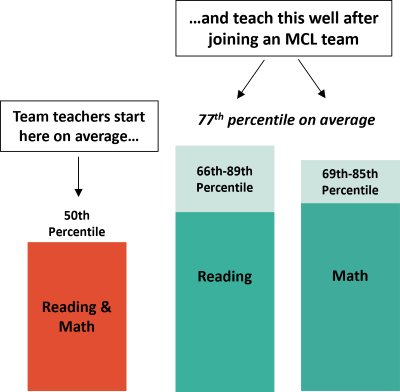

Third-party studies have found that, on average, teachers who joined Opportunity Culture® Multi-Classroom Leader® (MCL™ ) teams moved from producing 50th percentile student learning growth to 77th percentile student learning growth in both reading and math.

- A 2018 study looked at implementation in three early Opportunity Culture® districts

- A 2021 study looked at a Texas district’s outcomes during the 2020–21 pandemic year

In the Texas study, the researchers highlighted how positive the results were for English language learners and students considered socioeconomically at risk—particularly notable during a pandemic.

When we apply the method of Stanford researchers* to these results to convert the data into years of learning, we see that they equate to an extra half-year of learning for students each year, on average—when an educator in the MCL™ role with prior high growth leads the team. Some MCL™ teams in these studies had teachers in the Team Reach Teacher™ role, as well.

Averaging the two studies, the extra learning gains that students on MCL™ teams make each year would have more than made up for Covid-related learning loss or “unfinished learning,” (as estimated by McKinsey & Company for students nationally from March 2020–May 2021). And in non-Covid years, students would make far more learning growth than they otherwise do, on average.

Research Studies and the Opportunity Culture® Principles

The studies affirm the importance of the five Opportunity Culture® principles, which Opportunity Culture® districts and schools must follow:

- Reach more students with excellent teachers and their teams. The studies show how important teaching team leaders in the Multi-Classroom Leader® role, who are selected based on prior high-growth student learning, are as the cornerstone of Opportunity Culture® implementation. In the Brookings-AIR study, 100% of these team leaders produced student growth in the top quartile of teachers prior to taking the MCL™ role. Critically, in the studies combined, teachers on an MCL™ team shifted their students’ learning growth into the excellence zone (top 25 percent), too, on average.

- Pay teachers more for extending their reach. Neither study examined the impact of pay on effectiveness, but in the Brookings-AIR study, the district in the study with the highest pay supplements for MCL™ roles also achieved the highest level of math and reading gains by MCL™ teams. Those in MCL™ roles earn a supplement that averages about 20% of base pay nationally; in Ector County, this ranged from 26% to 35% of base pay. Increasingly, Public Impact® is helping districts and schools use designs that pay more to team teachers who extend their reach directly, and to paraprofessionals who help them, given their outstanding results on MCL™ teams. The results show us that Opportunity Culture® designs can work for all adults, and their students.

- Fund pay within regular budgets. All districts in the studies funded Opportunity Culture® pay supplements entirely within regular budgets.

- Provide protected in-school time and clarity about how to use it for planning, collaboration, and development. In these studies, the team leaders for whom data were available led teams with a median size of five teachers (Brookings-AIR) or four (Ector County ISD, where all the MCL™ roles were “partial-release,” meaning the team leaders continued teaching their own class[es] of record for at least part of the day). Small teams make it possible to schedule collaborative planning and development time for the whole team as well as one-on-one planning and feedback time for the leader and each team teacher.

- Match authority and accountability to each person’s responsibilities. In the Brookings-AIR study, the two districts that assigned clear accountability to the MCL™ role for all the students served by their teams had the strongest academic gains for those in this role. Public Impact® is continuing to explore how to measure the level of authority and formal accountability.

Using the method, we see that converting the data into years of learning equated to an extra 0.2 to 0.8 years of learning in reading and an extra 0.3 to 0.7 years of learning in math.