By Jeremy Baugh, February 15, 2021

In 2015, when I came to Lew Wallace Elementary in Indianapolis Public Schools as its fourth principal in four years, the community referred to the school as “Zoo Wallace,” and families openly expressed disappointment in being placed there.

Still, after sending out flyers and emails and making calls home about our meet-the-teacher night, I was shocked to have only one parent show up. In my 10 years as a principal, I had never seen anything like it.

Like the parents, teachers were demoralized and disengaged. One day, the school’s only other leader, an instructional coach, and I wanted to ask a quick question of some teachers. But at 3:30, just five minutes after the kids left for the day, the teachers had all disappeared, too.

And to many students, the school felt harsh. In that first year, over 300 kids were suspended—out of 500 students total. Our transiency rate was as high as 70 percent. The school had more than 90 percent of students receiving free and reduced-price lunch, an incredibly high amount of student trauma, and many newly resettled refugees. With multiple fires happening daily that needed our attention, we were pulled away from what really mattered—students, families, and great outcomes for kids.

By the end of the year, about 50 percent of the staff left.

Fast-forward five years: Despite the pandemic, Lew Wallace is thriving, and I’ve taken the lessons I learned there to another IPS school. What turned things around?

Support, Support, Support

It became clear that for me to successfully lead the school and focus on student outcomes, every single student and teacher needed to feel supported. That wasn’t possible in a building with just a principal and instructional coach, and having top-down leaders wasn’t going to work after so many difficult years for the staff. The school needed leaders at every level, listening to voices from within that could help us understand the roots of our problems. And we needed to get as many great teachers in front of kids as we could.

After my first year at Lew Wallace, the district planned to implement Opportunity Culture® in several schools in the transformation zone. We opted in, and by continually refining our plans over subsequent years, the school made leaps in academics and became a place of pride for families.

In an Opportunity Culture®, schools restructure roles, schedules, and budgets to extend the reach of excellent teachers and their teams to more students, for more pay, within recurring school budgets—all centered around the role of multi-classroom leaders, or MCLs.

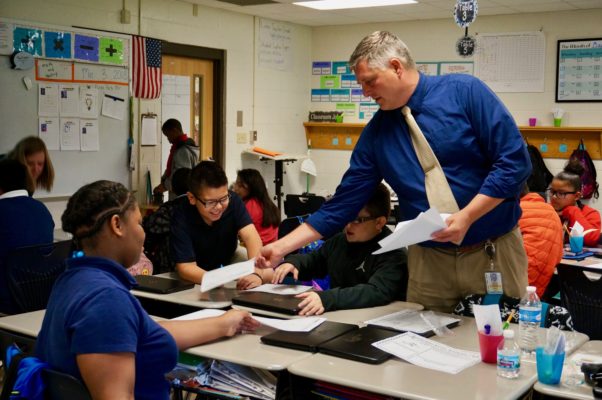

MCLs lead a small teaching team—at Lew Wallace, generally no more than six people—providing instructional guidance and frequent, on-the-job development. Carefully selected for their record of high-growth learning and competencies in adult leadership, MCLs co-teach, model instruction, observe and provide feedback, and pull small groups, all according to the needs of each teacher on their team.

Redesigned schedules provide plenty of time during the day for MCLs and team teachers to plan and collaborate individually and together, and for MCLs and school administrators to meet weekly as the instructional leadership team. The assistant principals and I could coach the MCLs, so that everyone in the building now had support. And because multi-classroom leaders are accountable for the success of their team members, they’re seen not as people there to evaluate but to build teachers up. MCLs earn substantially higher supplements—up to $18,300 in IPS—funded through reallocations of the school budget. Research shows that teachers in other districts produced strong learning gains after joining MCL teams.

We also used some other Opportunity Culture® roles that provide support for MCLs and the teaching team. In an Opportunity Culture®, some MCLs teach their own class for part of the day, so yearlong, paid teacher residents and advanced paraprofessionals known as reach associates support them, taking on noninstructional tasks, leading small groups, and leading the class when the MCL goes to plan or observe or co-teach in team teachers’ classrooms.

To determine how to implement an Opportunity Culture®, each school creates a design team that includes teachers. Our team spent a year designing our implementation plan based on our data and results from the end-of-the-year school climate surveys.

To be able to prioritize students and their outcomes, we wanted to focus on creating a positive school culture, building our school’s leadership capacity, and creating a schedule that supported our instructional priorities. Opportunity Culture® married those ideas.

We saw that multi-classroom leaders could bring instructional support and guidance to their teams, and paraprofessionals could provide the support needed to keep class sizes manageable so students could receive support as individuals and small groups. And with 50 percent of our staff gone, we had the flexibility to fill their positions with Opportunity Culture® roles.

The multi-classroom leader role specifically made a difference compared to the previous instructional coach roles. A coach will try to coach the entire school, and that’s just not feasible—you have to have a small number of people to reach, so we try to maintain it around six teachers on a team for multi-classroom leaders.

Super Scheduling

Next came right-sizing the schedule; we created a high-level master schedule so reach associates and specialists knew when to pull students, plus a schedule of moving parts showing where every educator is throughout the day, so other educators know when they can get support. I’ve found that one of the most important things school leaders can do after careful hiring is get the schedule right.

Throughout this process and the school year, we ensured that we had ongoing, clear communication about what was coming and how it would help everyone.

Distributing the Leadership

The biggest change due to Opportunity Culture® is the distributed leadership—having multiple leaders in the building to support teachers, rather than being dependent on the principal and assistant principals to provide it all. That means we went from two leaders when I started to 10 or more leaders in the building easily identified by other teachers as approachable, supportive instructional leaders. One of the best things that people talk about when others come in to interview is the collaboration and support that they feel every day.

All our Opportunity Culture® roles create an internal pipeline of strong educators as well—from the start of careers onward: Adding the roles of reach associates and teacher residents meant we could bring in great people and train them in our way, and teachers with great results on MCL teams have the chance to become MCLs themselves. Many MCLs love the role because it expands their leadership without taking them out of the classroom, but for those who aspire to a principalship, the role prepares them to be great instructional leaders of their building. One of our teachers, Jessica Smith, became an MCL, and then an assistant principal at Lew Wallace, while another former MCL, Brandon Warren, is an assistant principal at my new school.

Culture Change = Dramatic Improvements

With this strong support in place schoolwide, our statistics and our culture changed dramatically. In my third year, we were able to retain 97 percent of staff. People wanted to be here, so when we had a teacher vacancy, we had 150 applicants. In our staff survey, 85 percent of our people loved our multi-classroom leader roles. It definitely became part of the culture to have coaching support and to have the mindset that we’re all growing, we all have something to work on, and we’re going to do that together and make this a better place.

How much better?

We went from over 300 suspensions in my first year to around 50 suspensions in my fourth year, and we met our goals for reducing the disproportionate suspensions of special education and African-American children.

Academically, our kindergarten went from 32 percent on track at the end of the year to 82 percent. We saw huge growth in third grade.

When I arrived in 2015, we were the second-lowest-performing school in the district. In March 2019, we showed the sixth-highest growth in math on our state standardized assessment.

Like the teachers, kids now wanted to be at Lew Wallace. I always said I don’t want kids running out, I want them running in. That first year, I couldn’t find a single teacher at 3:30 to ask a question and now, on the last day of school, they’re all huddled outside at the buses waving, with tears running down their faces, and high-fiving kids, whose own tears show how much they value their teachers’ nurturing and loving relationships.

And what about parents? Four years after that one parent showed up to meet the teachers, we hosted a physical education night at which we displayed students’ artwork, and 225 families—not individuals, but entire families—showed up.

Jeremy Baugh is principal of Brookside School 54 in Indianapolis Public Schools.

For more, read and watch:

- High-Touch At-Home Learning? That’s the Plan in Indianapolis School

- How Opportunity Culture® Helps Schools Retain Teachers

- How Opportunity Culture® Lives Up to Its Five Principles

- Set Clear Expectations for Support to Reach Goals

Note: Public Impact® and Opportunity Culture® are registered trademarks; Multi-Classroom Leader®, MCL™, and Reach Associate™ are trademarked terms, registration pending.