By Philip Steffes; first published by EducationNC, December 5, 2019

How can kids learn when they’re not in the classroom?

That’s the issue I confronted when I arrived at Albemarle Road Elementary in Charlotte four years ago. Despite teachers who truly cared about their students, we had far too many suspensions.

And students were struggling. When I first came here, 95% of our teachers had been in the red — not meeting student growth targets — in literacy for multiple years.

With a brand-new Opportunity Culture® structure and paid summer time for Multi-Classroom Leaders (MCLs) to plan a new school-wide behavior program, we began to change those numbers — and with continued evaluation and adjustment of our efforts, the school’s shifts have been dramatic.

First, our short-term suspension rate dropped from 12% in 2014 to 3% in 2018. We reduced our out-of-class referrals — when teachers send students to the office — by about 63%.

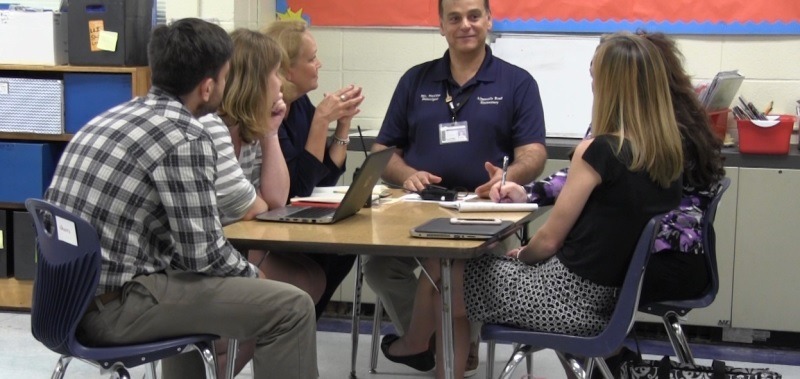

Does that mean we have a lot of unruly children now in our classrooms? No. That happened because teachers now have MCL support, and the support of the structures they created, to lead calm classrooms. MCLs lead small teaching teams with intensive support on all aspects of instruction and classroom management. Teachers now had MCLs coming in to say “let me show you how; let me give you some strategies so that you can build a relationship with students.”

Second, from 2015 through 2018, the school exceeded growth every year, pulled up its “F” end-of-grade reading score, and went from having a school performance grade of 47 up to 64, giving the school a high “C” grade.

The school has a student population that faces many challenges: Only 14% of kindergartners enter at grade level and 61% of the students come from economically disadvantaged households. Helping teachers understand these students and build relationships with them was a crucial element of MCLs’ leadership.

In that first year, with the new behavior program in place, teachers turned first to their MCL for help with classroom management situations. That gave MCLs a good opportunity to do some real-time coaching, helping teachers think through their response to an issue and what they could do differently.

In a school this large, you’re going to have issues with behavior, but we still had too many. So we needed to make sure that we had clear expectations: What do we do in our halls, our cafeteria, on the playground, in the bus lot?

The MCLs and their teachers defined expectations, then created a behavior matrix per class and posted it around the school. Each day for the first 90 days, there was a point system for the whole class.

In the second 90 days, students went to individual point systems, with a celebration each month for those who hit the bar. Students were challenged each month to monitor and track their individual daily points, with the monthly bar to participate in the celebration increasing from 75% of possible points in January to 95% by May.

But while those numbers apply to the students, the change is not in what we expect of students — but of teachers. It’s defining exactly what the expectations are, articulating those, and then moving toward holding the teachers accountable for following through on expectations.

That was a real shift for a lot of us. We will naturally redirect children; now, we were having MCLs move toward redirecting adults. Their feedback to their teaching team may mean saying, “I notice that your students are doing this — remember you need to look at the matrix in the hall so we can adjust to it.”

With calmer classrooms, our teachers began to see more student learning growth as well, through the support of our instructional team of leaders — myself, my assistant principals, and our MCLs. Teachers know that we’ll be in the classroom helping them. It’s intensive support — all of us, including myself, will teach with them, sometimes stopping their teaching in real time to say, “Let’s try it this way.” Their MCLs will plan with them, practice teaching a lesson with them, model a lesson, co-teach, and give feedback.

Collectively we succeed, and collectively we handle our setbacks. That’s the way we were going to move things, and we did.

This year, I’ve left the staff at Albemarle Road Elementary to take on a new challenge, leading a school in its first year of Opportunity Culture® implementation. I’m excited and confident in what I left behind. I know the staff and I established strong structures that will continue to positively impact teaching and learning within the school.

Philip Steffes is principal at Palisades Park Elementary in Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools.

Note: Public Impact® and Opportunity Culture® and Multi-Classroom Leader® are registered trademarks.