By Sharon Kebschull Barrett, March 27, 2020

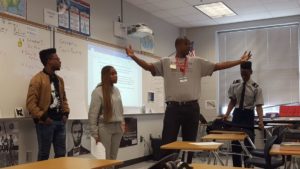

For Tu Willingham, distance teaching and team-leading are already well underway. A history multi-classroom leader at Banneker High School in Fulton County (Georgia) Schools who was a 2017-18 Opportunity Culture® Fellow, Willingham has tackled the early weeks of the school shutdown with strong team leadership and ideas about what can make distance learning work.

Everyone needs time to adapt to the reality now, Willingham said, noting that he felt inundated by the news until this week, when he felt better able to “move on and just accept the fact that this is a difficult situation that we have to get through.”

In the early days, Willingham focused on helping his teaching team get their digital platforms set up with lessons, lesson plans, and links to their instructional sites.

His team is taking the instructional work in steps: “I’ve got so many meetings for about 30 minutes just to check in. A lot of my phone calls and sessions have been ‘Hey, just deliver an assignment to students.’ … Next week we’ll start working on improving the quality of the assignments and making sure they are robust, but our goal this week was, let’s just get them something and let them know we care, and that this work is important.”

While his students are on spring break next week, Willingham will focus on creating robust performance tasks for his students that the teaching team can practice before delivering to students.

Banneker expects students to get live instruction once a week in each core subject, one subject per day.

Willingham wanted live classes twice a week, he said, but “they want us to stick to that schedule because they don’t want students to be overwhelmed. … Now, they are working on their assignments all week, but in terms of the synchronous sessions, ours is always on Thursdays,” he said.

“I encourage the teachers to chat it up with the students a little bit—‘how was your day?’ Some of the students are very anxious, some of them are scared, some of them are just not in a good mental state. So I said, ‘Before you start class, make sure you have a good rapport with them—talk about something funny that happened, etc.—then get your class started.’ We’re trying not to go over 60 minutes for the first session; 45 minutes is ideal.”

Willingham’s students have his phone number; many used it when they needed help just getting logged on. And he asks students to help one another; when he had a session in which many students failed to show up, he had those who did attend each contact two students to make sure they knew how to log on.

Students can email or text him, or use Remind any time they have questions. “Our district requires that we be accessible between 8 o’clock and 4 o’clock, so we’re required to respond to emails immediately, and/or phone calls, and make sure we communicate with the parents.”

Among Willingham’s suggestions for schools:

—Limit the number of digital platforms used (echoed by MCLs in other districts). Although that limits teachers’ autonomy in using platforms they like, it helps students who now may have five platforms they must navigate—it’s “like an octopus on roller skates,” Willingham said. “We should have a one-stop shop…less clicks, the more learning takes place.”

—Continue to hold students accountable when possible, with some extra measures of grace. That requires extensive communication with students and families. Teachers check that every student has logged in every day, and call home if not.

“Our parent phone calls have been numerous, and a few students just simply don’t have devices and/or Internet access…our principal talked about how we’ve got dozens of students that are living in extended-stay rooms, like four, five, or six to a room; no Internet access. You know, whatever happens in society is going to be multiplied in our school, so we’ve got to deal with that in a very gentle way and assume that the kids are trying.”

—Maintain what works and keeps connections strong. Throughout the shift to at-home teaching, many routines continue, such as his team meetings three days a week and meetings of the instructional leadership team.

—Plan now for doing this long-term. “We already are assuming that there won’t be any brick-and-mortar school this year, so [at our team meeting] I’m going to start talking about long-term plans for the rest of the year—how are we going to give assessments, how we’re going to grade, and starting to be a little more creative about the assignments.”

After spring break, Willingham will begin observing and coaching his team while they teach online. His routines of coaching, co-teaching, modeling, and leading the team in data analysis really shouldn’t change if work stays remote, he says; the main work is shifting strong in-person instruction to strong distance instruction—and learning as they go, such as by trying to avoid overly teacher-led classes.

“Even in my new session that I did last week, I watched a recording and I was like, “whoa, I’m doing a whole lot of talking,” and that’s just to be expected [at first]. But there are some tools that you can implement into Microsoft teams where the students are doing the work,” he said. Ultimately, he tells his teachers, “you’re getting an opportunity to put more arrows in your quiver. So just look at it as an opportunity to perfect your craft, because this is where it’s going. I mean, we’re still going to have brick-and-mortar schools, but I guarantee you the digital element is going to be exponentially bigger from here on out.”

Through communications and food and technology distributions, the district “is doing a very good job of making our students and families feel loved and wanted. They’re going above-and-beyond, so I’m very proud of our district and what they’re doing. Everything is not seamless, but of course, this is uncharted territory,” Willingham said.

“I think the biggest lesson that our students are going to learn from this is that the learning doesn’t stop. I think the fact that we’re reaching out and going overboard—to make sure that students get their assessments, their lessons, and make sure they’re learning—I think it lets them realize that ‘hey, this education stuff is important,’ like, even in the midst of all of this, we still have a job to do. So hopefully, our students will become better citizens after this, at least.”

This column is one of a series of interviews about the COVID-19 shift to at-home teaching:

- For This MCL, A Week of Team Planning and Parenting

- Keep Doing What Worked: Advice for At-Home Learning

- In Charlotte, Keeping Connected to 212 At-Home Students

- Consistency and Care: Confronting COVID-19 in a Rural School Community

- Spreading Support in Vance County During At-Home Learning

- From Start to Finish, A Focus on Relationships During At-Home Learning

- High-Touch At-Home Learning? That’s the Plan in Indianapolis School

- In Arizona, Turning Vulnerabilities Into Strengths as Teaching Goes Home

Note: Public Impact® and Opportunity Culture® and Multi-Classroom Leader® are registered trademarks.